I had a contact from a chap called Steve Baker, recently, with a fascinating story about the jungle survival kit issued to the SAS. He sent me some fabulous pictures, and then more, after I said I wanted to see details… it’s an epic account of a true british military hero, dubbed the Grand Daddy of the SAS.

Who took a Milbro catapult for use in jungle survival.

The rest is all his, with all but nil edits.

The Milbro Slingshot – As used by the SAS

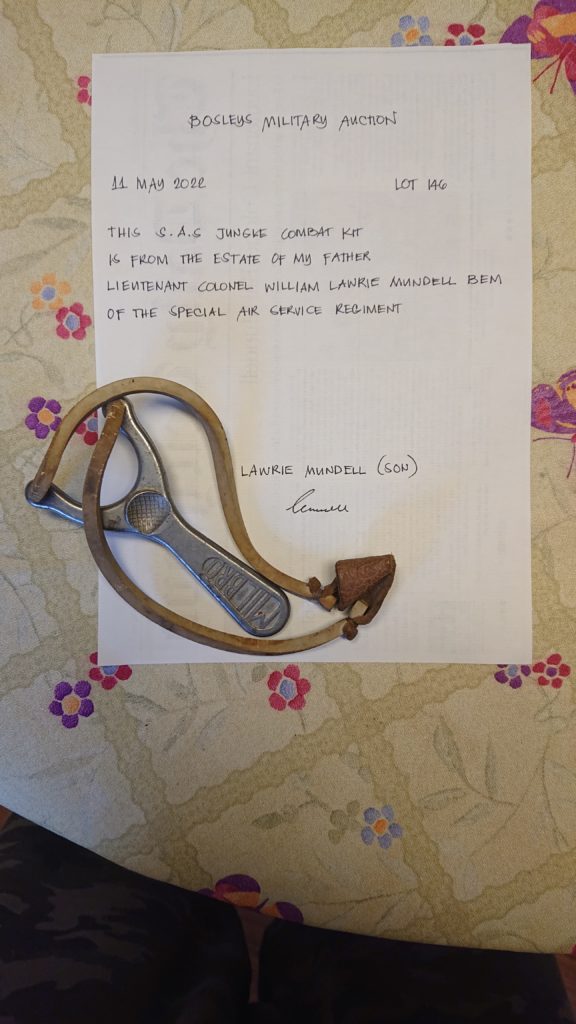

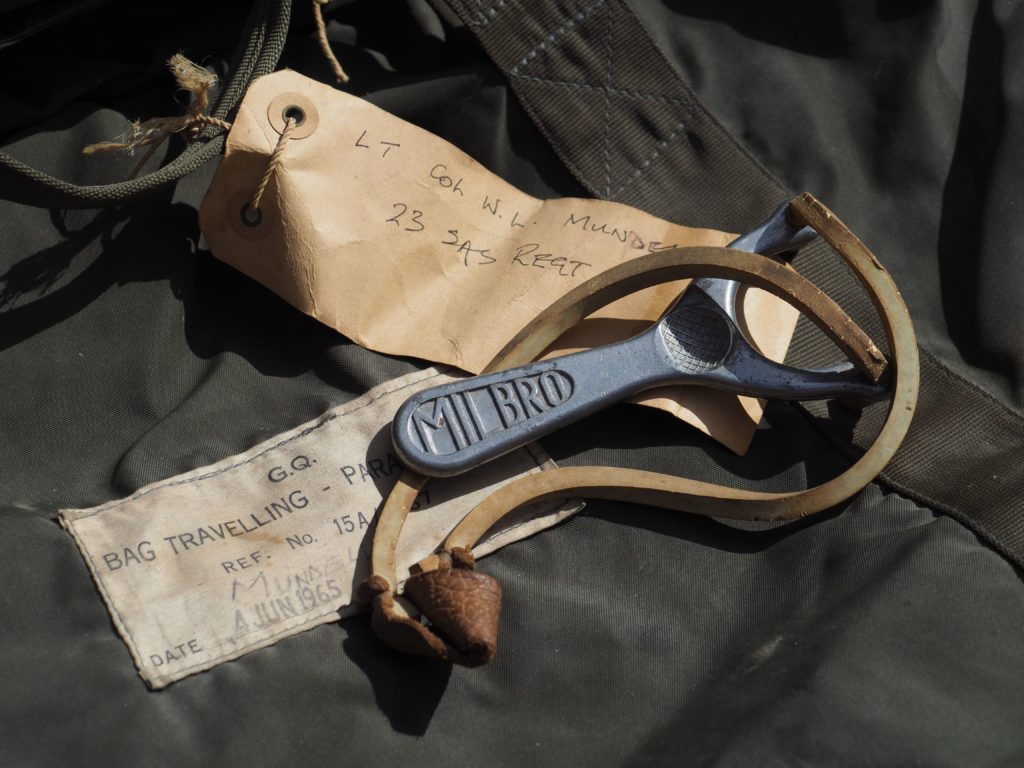

In 2022, I came across an article mentioning an upcoming military auction. The sale’s highlight were 32 lots that had belonged to Lieutenant Colonel William Mundell, BEM, who was the Longest Serving Member of the Special Air Service. (SAS)

William Mundell sadly passed away in 2020 aged 88, General Sir Peter Edgar de la Cour de la Billière, K.C.B., K.B.E., D.S.O., M.C. & Bar, paid him the following tribute:

‘He was among the most outstanding soldiers I have had the privilege to serve with.’

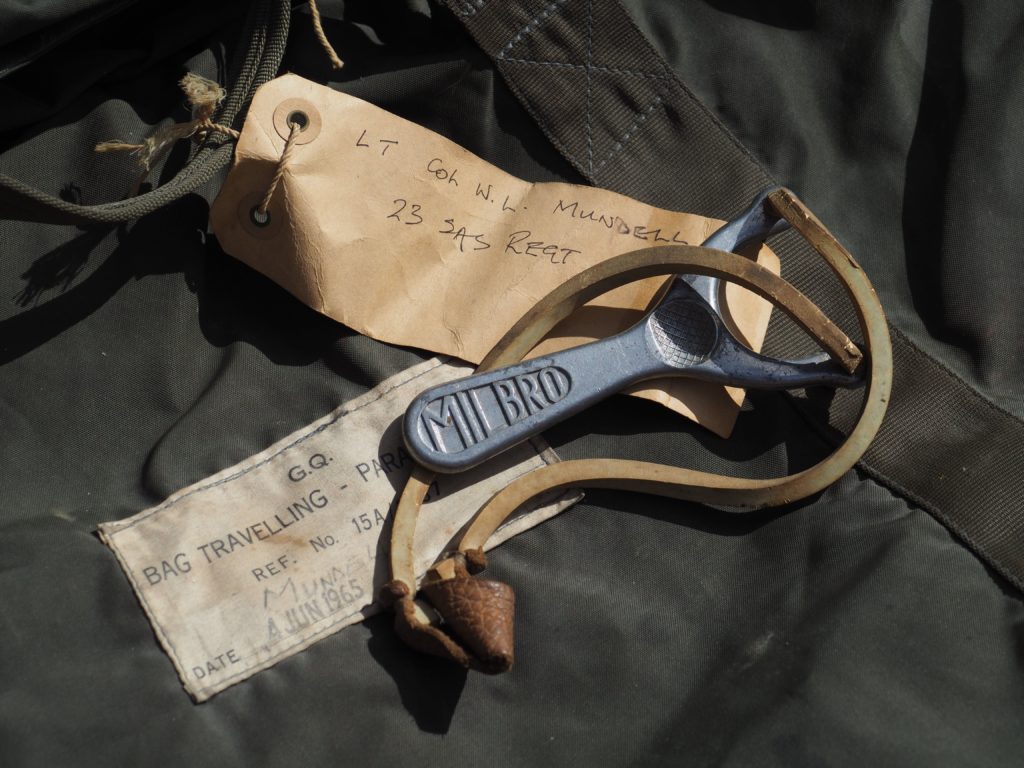

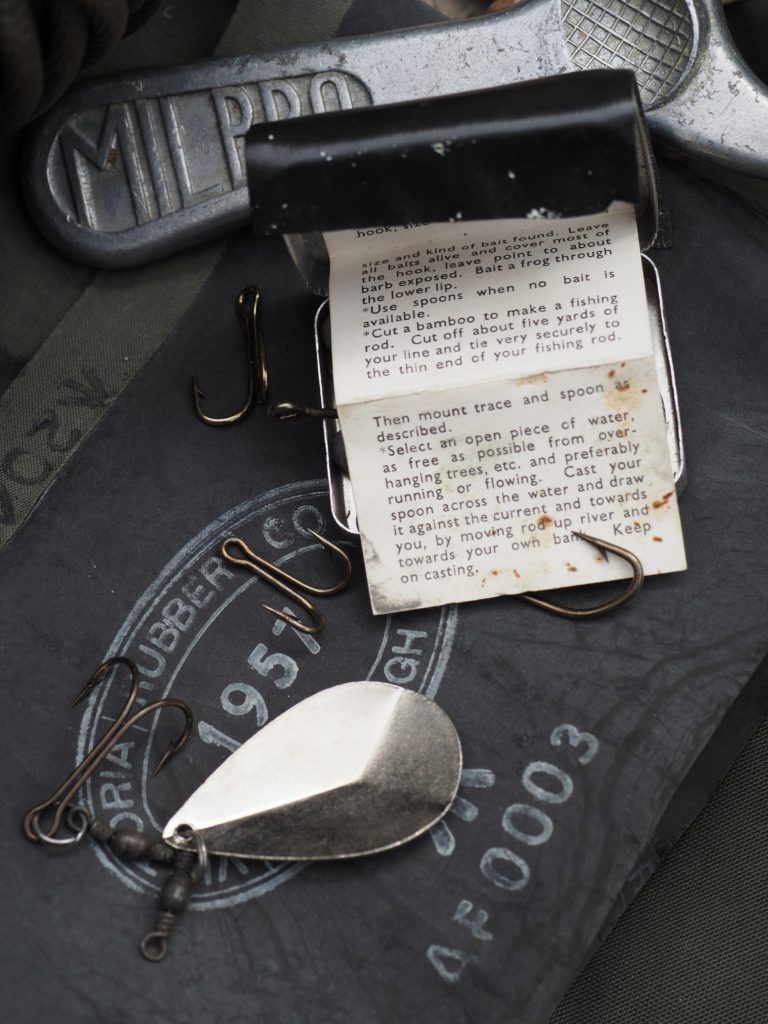

The auction items included previously unseen and uncensored photographs, badges, uniforms, and other memorabilia. One particular lot that interested me was his jungle combat kit. The kit comprised a British military-issue hammock, lightweight sleeping bag liner, mosquito net, waterproof bags, webbing straps, snake bite kit, fishing line & wire leaders, a tin of hooks & spinners, and a Milbro slingshot, all stored in his parachute bag. It’s surprising to think, that the humble Milbro slingshot would be such an invaluable item in a SAS trooper’s jungle combat kit!

I became interested in militaria at a young age, listening to my grandad’s stories from his time in the British 8th Army. He fought through the deserts of North Africa, and participated in the invasion of Sicily and mainland Italy, including the battle of Monte Cassino. He ended his service in Austria with the liberation of a prisoner-of-war camp. Throughout the years, I’ve collected a diverse range of military-related items from the 20th century. However, when I saw this auction and thought I might be able to own some genuine Special Air Service history, I had to place a bid. Thankfully I won, and now I’m eager to share this amazing man’s story and some of his jungle equipment with a wider audience.

The following is a brief account of the career of this remarkable man who turned the world’s jungles into his home by using the items you can see in the images.

Lieutenant Colonel William Mundell, BEM, holds the record for the longest-serving member of this elite regiment. He served with distinction for 36 years from 1952 to 1988 with both 22 and 23 SAS Regiments. Renowned as a jungle warfare specialist, he led a significant four-month patrol into the Sarawak region during the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation, earning a decoration for his exceptional service. He also received a ‘mention’ for his role in the Malaya campaign. Known for his extensive knowledge, he often provided lectures on jungle warfare tactics and the unit’s history, even in his advanced age, earning him the nickname ‘Grandad of the Regiment.’

William Lawrie Mundell was born in Maybole, Ayrshire, on July 1, 1931, the son of an army veteran seriously wounded in the First World War. He was one of three brothers, all of whom served in the Army, with William seeing action in Korea during his National Service in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. In 1952, he was demobilised, but re-enlisted into the newly re-formed SAS Regiment in Glasgow to fight in the Malayan Emergency (1948 – 1960) It was during this time that he developed a lifelong affinity for jungle warfare.

A skilled jungle fighter, tracker, and instructor, he remained calm under pressure and was comfortable in the wet, disease-ridden rainforests teeming with mosquitoes and leeches. Surviving was often the primary focus during operations; men typically lost about 10 pounds over fourteen days. Their clothes rotted, they suffered from severe jungle sores, grew pale due to the constant twilight, and frequently experienced heat exhaustion. They relied on a daily diet of Paludrine tablets to prevent malaria and had to spend a significant amount of time removing leeches from their body. His advice to recruits was to “make the jungle your friend.”

After ‘Operation Helsby’, an offensive in the River Perak-Belum valley, during which B Squadron (soon to become 22 SAS Regiment) carried out the first parachute drop, it was evident that a dedicated training program was necessary. In the spring of 1952, a series of experiments began, in which Mundell excelled, pioneering many new ideas. Due to the extremely hazardous and often fatal nature of jungle parachuting, numerous new techniques were developed. One of these involved using ropes to descend to the ground, due to the parachutes getting entangled in the trees or jungle canopy. Advances in jungle parachuting continued throughout the 1950s, culminating in 1958 when thirty-seven men left the aircraft in only eighteen seconds during a practice jump.

During the 1960s, the SAS was severely understaffed, and its workload was so heavy that men often found themselves on multiple back-to-back tours in areas thousands of miles apart. The Indonesian Confrontation (1964 – 1966) and the Aden Emergency (1963 – 1967) were key operational areas. Many servicemen were deployed on four-month tours in Borneo, followed by two weeks of home leave, then four months in Aden, and then back to Borneo.

In 1963, 22 SAS were sent to Borneo under the overall local command of Major General Walter Walker. Indonesia was sending troops and insurgents across the Sarawak border to destabilise the region. Walker, impressed by the SAS’s performance in Malaya, was convinced that the Regiment’s expertise, gained from their time there, would prove decisive.

The primary objective was to protect the 700-mile-long Sarawak border. Mundell, now a Sergeant, led a SAS fighting patrol in Sarawak along the extensive and porous border with Kalimantan. The terrain in this area was one of the most unwelcoming in the world, characterised by dense mountainous jungle and expansive, nearly impenetrable swamps. Remarkably, the patrols proceeded with great care to avoid leaving any traces. They deliberately walked off the existing paths, refraining from hacking through the vegetation. Sometimes, they even replaced leaves and grass to eliminate evidence of their presence.

Moving through the jungles of Borneo was of course extremely challenging. Much time was spent, just waiting and listening for signs of the enemy, sometimes for as much as 20 out of 30 minutes. The mental pressure was intense, as visibility was often limited to just a few meters, and around every corner, there may be an enemy ambush. Most of the time, the routine was tough – no lights, no smoking, and no hot food. Canned sardines became very popular. When moving, silence and leaving no trace became crucial. Whispering was standard practice. Some men even whispered when they were back in England, so ingrained had the practice become for them, mentally.

Mundell was also involved in several secret long-range cross-border operations. He had a talent for intelligence work and was responsible for recruiting and training agents from local tribes to work as border scouts. Their main task was to gather information about the activities of Indonesian Army units. The long-range patrols were assigned to locate Indonesian supply lines and bases and to identify suitable ambush sites. These patrols typically lasted three weeks, during which all supplies were carried by the patrol members. As the patrols moved deeper into enemy territory, their supplies were reduced to allow for faster movement, with each man eventually carrying only fifteen pounds of dehydrated rations, water bottles, survival kits, and ammunition on their belt.

Full cross-border operations by British infantry units began in July 1964. These operations were guided by SAS troopers and remained top secret for a long time due to political sensitivity about putting British troops into a country not technically at war with Britain. These covert missions were known as ‘Operation Claret’. For his part in these daring operations, Sergeant Mundell was awarded the British Empire Medal.

B.E.M. London Gazette 21 August 1964. The original recommendation – from Lieutenant-Colonel Woodhouse, CO 22 SAS – states:

‘Place – Sarawak 8 April-21 August 1963.

Patrol Commander – Sergeant Mundell commanded an SAS patrol in Sarawak close to the Kalimantan border, for over four months. His outstanding personality, diplomacy, and flair for intelligence work enabled him to organise a number of agents, which he recruited from the local people, and by so doing he was able to gather detailed information regarding the activities of an Indonesian Army detachment across the border in Kalimantan.

In the early 1970s, Mundell served with the SAS Regiment (TA) and was promoted to Regimental Sergeant Major. He saw action in Oman against Communist-backed insurgents from nearby Yemen who were trying to overthrow the Sultanate. However, in 1972 he was discharged as Warrant Officer Class 1 as he was appointed to a commission. After that, he held training and senior quartermaster positions until he retired in 1987 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

Mundell died on 22 February 2020 and his funeral was held at Hereford Cathedral, with over three hundred former comrades and friends attending.

In his eulogy, Major-General Arthur Denaro at his funeral said the following:

“It was that steady look, and the quiet steel in his voice that made people sit up and take note, no expletives, always softly spoken, but when Bill spoke, people listened, for it counted. It was not that people were frightened of him, more they were afraid of letting him down. His expertise, his quiet confidence, and his hugely inspiring example were what people responded to.”

Lieutenant Colonel William Mundell BEM was admired and respected by all who served with him. One colleague described him as “meek and mild and made of steel”, another as “the consummate professional – everyone wanted to be in his patrol”.

Steve Baker

(and he took a Milbro with.. Ed.)